The income tax has made more liars out of the American people than golf has. - Will Rogers

The wages of sin are death, but by the time taxes are taken out, it's just sort of a tired feeling. - Paula Poundstone

To put it mildly, tax talk is hot these days and of course with it comes uncertainty as to the value of the income exemption on municipal bonds. The administration has floated the so-called "Buffet Rule" which would enforce a minimum effective tax rate for wealthy individuals along with the draft Debt Reduction Act of 2011 that would involve automatic spending cuts, including ones on tax preferences on interest. Needless to say, many muni market participants are not fans of the additional uncertainty of the value of tax-exemption.

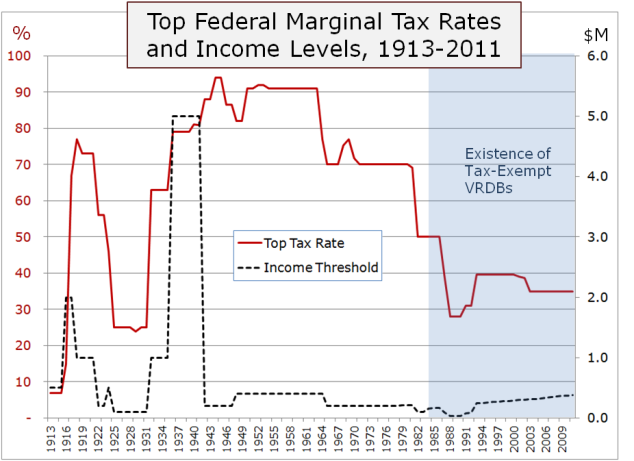

But really how new is this? The chart below shows historical top Federal marginal tax rates from the inception of the income tax in 1913 to today.

Source: National Taxpayer's Union

A few interesting things to note. First the highest federal marginal tax rate was often well north of 50% from 1932 through 1986. For most of that period this rate kicked in for those earning more than $200k to $400k, though during the late 30s and early 40s it was reserveded for those Rockefellers of the day taking down more than $5 million. Next, note the creation of tax-exempt VRDBs coincided fairly closely with a big drop in the top Federal Marginal Tax Rate (FMTR) with the Tax Reform Act of 1986.

How has this changed the value of tax-exempt bonds? This is at best difficult to say as the municipal market has changed so dramatically (along with other financial markets) during the period after the Tax Reform Act of 1986. Since then, the top Federal Marginal Tax Rate (FMTR) in relative terms simply hasn't changed much.

Once you remove the effect of rate levels themselves we find that the very approximate relationship between tax rates and tax-exempt / taxable ratios in the variable rate market are

Tax-Exempt / Taxable Ratio = (1 - TopFMTR) + 2%

Depending on the data set you use and how you control for rates you can get that 2% to move around quite a bit but we find this a reasonable rule of thumb when rates are in a normal range. Of course they haven't been anywhere near normal for many years since Fed Funds has been effectively zero.

Today the true tax risk could go in either direction. The threat of higher marginal tax rates on high earners would bode well for the value of tax-exemption, but proposals pushing a lower FMTR with fewer loopholes would likely hurt.

Tax risk is certainly real, now how much SIFMA/LIBOR swap do you need to hedge it?

Comments