"To confuse the model with the world is to embrace a future disaster driven by the belief that humans obey mathematical rules." - The Financial Modeler's Manifesto, Emanual Derman and Paul Wilmott

Recently I discussed new research by Andrew Ang (Columbia), Richard Green (Carnegie Mellon), and Yuhang Xing (Rice) that maintained that in the presence of transaction costs, advance refundings always destroy value to the issuer. Based on this conclusion the authors proceed to question the tax policy wisdom of allowing municipal borrowers to advance refund at all, a conclusion I believe is not universally popular in the public finance community for a number of sound reasons.

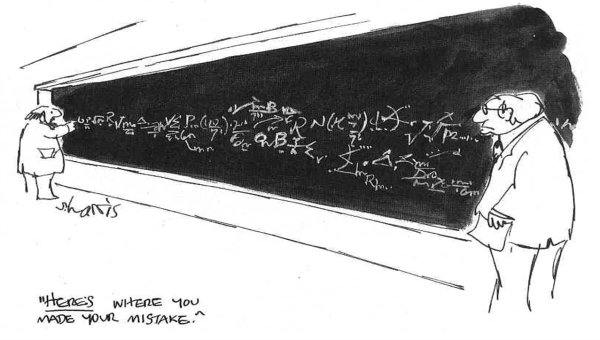

My first reading of the paper was cursory but on more detailed examination I find they make a mistake, big time. It’s a mistake that strikes to the core of their hypothesis, and it’s not really even a mistake in their public finance either. It’s a fundamental error in plain old financial modeling itself, in how they calculate “losses,” and ultimately in their conclusion. It’s a mistake I frankly am very surprised that finance professors would make.

The error shows itself unobtrusively in one seemingly non-controversial but foundational sentence on page 10 which goes both unnoticed and, for the paper's sake, tragically unexamined,

“We can represent the value of any security as the discounted expectation of its payoffs under the risk-neutral measure….”

In a word, WRONG. Dead wrong. Grade F (My dad the navy frogman was tough during homework review...) Where are the grad students and peer reviewers on this stuff? This seemingly innocuous statement naturally avoids detection by public finance practitioners because their jobs simply don’t require an intimate understanding of arbitrage-free (risk-neutral) pricing, for reasons we’ll see more clearly below. And it fails to trip the warning detectors of many financial theorists and academics because that lot is so steeped in the dark arts of asset pricing theory that such a statement is utterly unremarkable and unquestionably obvious. The theory is so established and ubiquitous in academic circles that it fails to even arouse the suspicion of its cultural adherents. And that culture, both academic and practical, chooses at its peril to forget the very tenuous and often unrealistic foundation on which it rests.*

But before unpacking the specific problem with Ang et al’s statement above I would offer that those keepers of the asset pricing mysteries (particularly those teaching our youth!) would do us all a tremendous favor by reading the Modeler’s Manifesto and abiding by its Modeler’s Hippocratic Oath,

- I will remember that I didn't make the world, and it doesn't satisfy my equations.

- Though I will use models boldly to estimate value, I will not be overly impressed by mathematics.

- I will never sacrifice reality for elegance without explaining why I have done so.

- Nor will I give the people who use my model false comfort about its accuracy. Instead, I will make explicit its assumptions and oversights.

- I understand that my work may have enormous effects on society and the economy, many of them beyond my comprehension.

Had the authors committed to and followed the Oath, their paper would be either very different or unwritten.

But back to their statement and it’s fundamental, fatal flaw. To correct their statement one would need to add a very simple but crucial qualifier, which for this paper ultimately renders the statement itself simply incorrect,

One can represent the value of any security as the discounted expectation of its payoffs under the risk-neutral measure IFF the risk-neutral measure EXISTS!

Without going into a lot of unnecessary minutia, the simplest way to assess whether risk-neutral valuation technology might apply to a given problem is to first assess whether or not the security in question is in fact hedgeable.** Hedgeability equals price-ability. Hedgeability is a prerequisite for constructing a risk-free and self-financing hedging strategy and such a strategy is an absolutely necessary prerequisite for any risk-neutral pricing theory to apply.

So how can we determine whether or not a callable municipal bond or bond option is hedgeable? We could ask a dealer. But that work is unnecessary because conveniently we can directly quote none other than the lead author of the paper himself, Andrew Ang, from some excellent research he got published all the way back in 2010. Though the research relates to municipal bonds impacted by the market discount rule, you’ll note that the section below applies to municipal bonds quite generically,

“Municipal issuers are unable to arbitrage the mispricing of…bonds. IRC §148 specifically prohibits arbitrage across municipal bonds and other types of bonds (for example, Treasury and corporate bonds) by tax-exempt institutions…. Unlike Treasury bonds, shorting municipal bonds is very hard because only tax-exempt authorities and institutions can pay tax-exempt interest. An investor lending a municipal bond to a dealer would receive a taxable dividend because that dividend is paid by the dealer, not a tax-exempt institution. Even if an active repo municipal market existed, it may be hard to locate a suitable municipal bond as a hedge because of the sheer number of municipal securities. Shorting related interest rate securities, like Treasuries and corporate bonds, opens up potentially large basis risk. Another reason arbitrage may be limited is because the trading costs are much higher than Treasury markets.”

- Ang, Bhansali, and Xing, Taxes on Tax-exempt Bonds Journal of Finance (2010)

Couldn’t have said it better myself. This paragraph provides exactly the reasons why municipal bonds are effectively unhedgeable. But the undeniable and incontrovertible consequence is that risk-neutral pricing theory therefore CANNOT apply. Ang 2010, where were you when Ang et al, 2013 did this research!?!?! The ultimate ramification for the paper is that the “loss” calculations the authors create, which they base entirely on (25+ year old) risk-neutral models using risk-neutral inputs, are figments of the authors’ highly educated imaginations. Unicorns are pretty too but they don’t exist, and existence is (I believe still) a really important feature if you’re using loss estimates to try to influence national fiscal policy.

I know that to some, the above may largely be high concept gobbledygook. The bottom line is this: "losses" must be relative to some value that is actually attainable, or else it’s very tough to realistically call them “losses.” So where’s the strategy whereby a municipality actually captures the value the authors characterize as loss? The research only mentions the use of devices such as interest rate swaps to hedge the rate risk an advance refunding otherwise eliminates. This is a reasonable answer for those tax-exempt entities who maintain the risk appetite, liquidity reserves, management expertise, legal authority, and political will to execute swaps. And could those borrowers who satisfy all of these criteria please raise your hand? Now how much of the over $1.5 trillion in outstanding, unrefunded, callable, fixed-rate muni bonds is on the books of those swap-happy borrowers with hands up? 10%? 5%? Now there’s a research question worth answering. And that question can be rolled into an investigation of the number of misleading press articles written and careers cauterized or destroyed due to the use of municipal derivatives. Here’s a case study contribution to kick off that new paper – my exchange with the editors of the NYT on their coverage of muni swaps.

Though currently the danger of thoughtful new reform of any sort being considered in Washington is remote (maybe get the SLGS window open first?), I maintain that should it ever occur, this paper demonstrates more an example of professors inebriated by the exuberance of their own quantitative verbosity than it does some new discovery that would inform the prudent revision of the Tax Code.

*See 'The Formulat that Killed Wall Street' for a unique and fascinating bit of research on the culture of financial modeling and its contribution to the financial crisis via the CDO market.

**From a variety of sources, "The lack of arbitrage is crucial for existence of a risk-neutral measure."

***For a truly excellent article describing the types of rate models that different players should use in their respective situations (including munis explicitly), see What Interest Rate Model to Use - Buy Side versus Sell Side.

Comments