We’ve written a number of articles talking about financial forecasting being a necessary evil, implied forward yields being miserable predictors of realized yields, and recently the inappropriate use of option pricing models (requiring market-based inputs) when doing refunding analysis. We even wrote a paper on it as we see a lot of misunderstanding by pubfin practitioners on this point.

But what I didn’t expect was for the press to actually make news out of it. Last week a financial advisor friend and (u)ncalculated risk contributor pointed out a short but important BondBuyer article written by Gary Siegel, who picked up on an economic letter published by the San Francisco Fed that re-iterates this theme. Now I’ve been known to critique the press from time to time, but have to give props to Mr. Siegel on this one.

In customarily gentle tones the Fed researches, Michael D. Bauer and Glenn D. Rudebusch of the SanFan Fed, say “policymakers should be cautious in relying on the expectations information in market prices…market-based expectations do not correspond exactly to real-world expectations because asset prices also reflect the compensation that investors require for making risky and somewhat illiquid investments.” For munis, “somewhat illiquid” definitely constitutes a glass-is-half-full descriptor. Plus munis are even more complicated because of their uncertain tax treatment, a significant risk to the investor.

Mr. Siegel in his Bondbuyer article goes on,

“…choosing an optimal policy under uncertainty involves two steps: (1) assigning probabilities to uncertain future outcomes depending on the choice of the current setting of policy, and (2) ranking the relative desirability of different policy choices by evaluating their expected benefits and losses. …a policymaker would use real-world probabilities to calculate the expected net benefits of a variety of possible policy actions, and then choose the policy action that maximizes that net benefit.”

So easy! And eminently sensible. And it happens to be exactly what we did in analyzing refunding policies in our paper identifying the best refunding policy yet known. And as we recently described, evaluating muni callables by both issuers and investors involves assigning real-world probabilities to refunding outcomes driven by the complicated and simultaneous dynamics of multiple yield curves, no small task.

Congrats to Mr. Siegel and the BondBuyer for picking up on an important piece of the forecasting and policy-making puzzle. Note we are not paid by the Bondbuyer in any way. Quite the contrary; think our 2015 renewal statement’s on my desk (we’d certainly take a subscription discount though…hint hint). But I don’t want anyone to get the mistaken impression that all we do is press bash here.

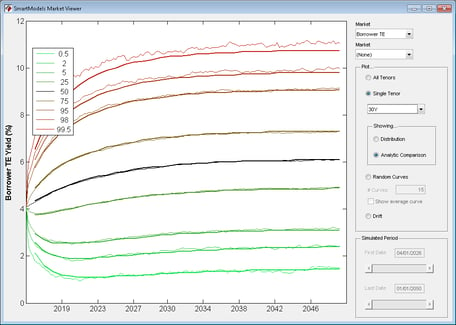

If you’re reading this the chance that you’re a central banker is relatively slim. However, you may well be in a position where you have to forecast financial variables (bond yields, perhaps?) in order to evaluate fixed vs floating, a 4% vs 5% coupon, expected muni hedge performance, a 7 year call feature, a refunding candidate, or even a broader financial policy. In any event, it’s the real-world expectations that matter.

Comments